I was doing laundry around 4 AM on a weekday morning. Typically I am much more organized — separating lights, dark, and white and towels from linens. This time I was rushing because my son needed to wear a specific shirt for school that day. So I took his white undershirts out of the washing machine and threw them in the dryer to wash the next load. I did not sort anything. I took a heaping pile of clothes and his shirt and washed the load on a short cycle. I hoped it would be washed and dried before he was scheduled to catch his bus to school. Fortunately, the clothes dried right before we left to catch the bus. As I took his shirt out of the dryer, I noticed my shirt was mixed in with his laundry. It was a green shirt now speckled with bleach stains.

I let out a long sigh and grabbed his shirt in a hurry. When I came back inside I took another look at the shirt. The new green and bleached t-shirt is a shirt I purchased from my best friend with her artwork on it. I didn’t throw it out. The way the bleach spattered on the shirt I tilted my head to the right and looked at it again. This accidental creation is much like how many of my friendships began. They’ve taught me true friendship’s complex and fragile nature. Understanding friendship and community is a journey, not a single destination. I am a student of this cause that continues to teach me.

To deliver these reflections with veracity I admit that my understanding of community was short-sighted. There was a time when I believed the framework of friendship began as two people became friends. I’ve learned this theory was wrong, but the deepening of my comprehension was not a linear process. The commencement of my study of community began with an unintended period of introspection. I found myself isolated while going through a devastating heartbreak. I wasn’t as engaging with my friends while I was in the relationship. The absence of our relational proximity mattered less than the effort I put into my relationship. I told myself I was as good of a friend as possible. I thought I was doing my best as a mother of a special needs child and soon-to-be married. My desire for closeness with my friends multiplied post-breakup.

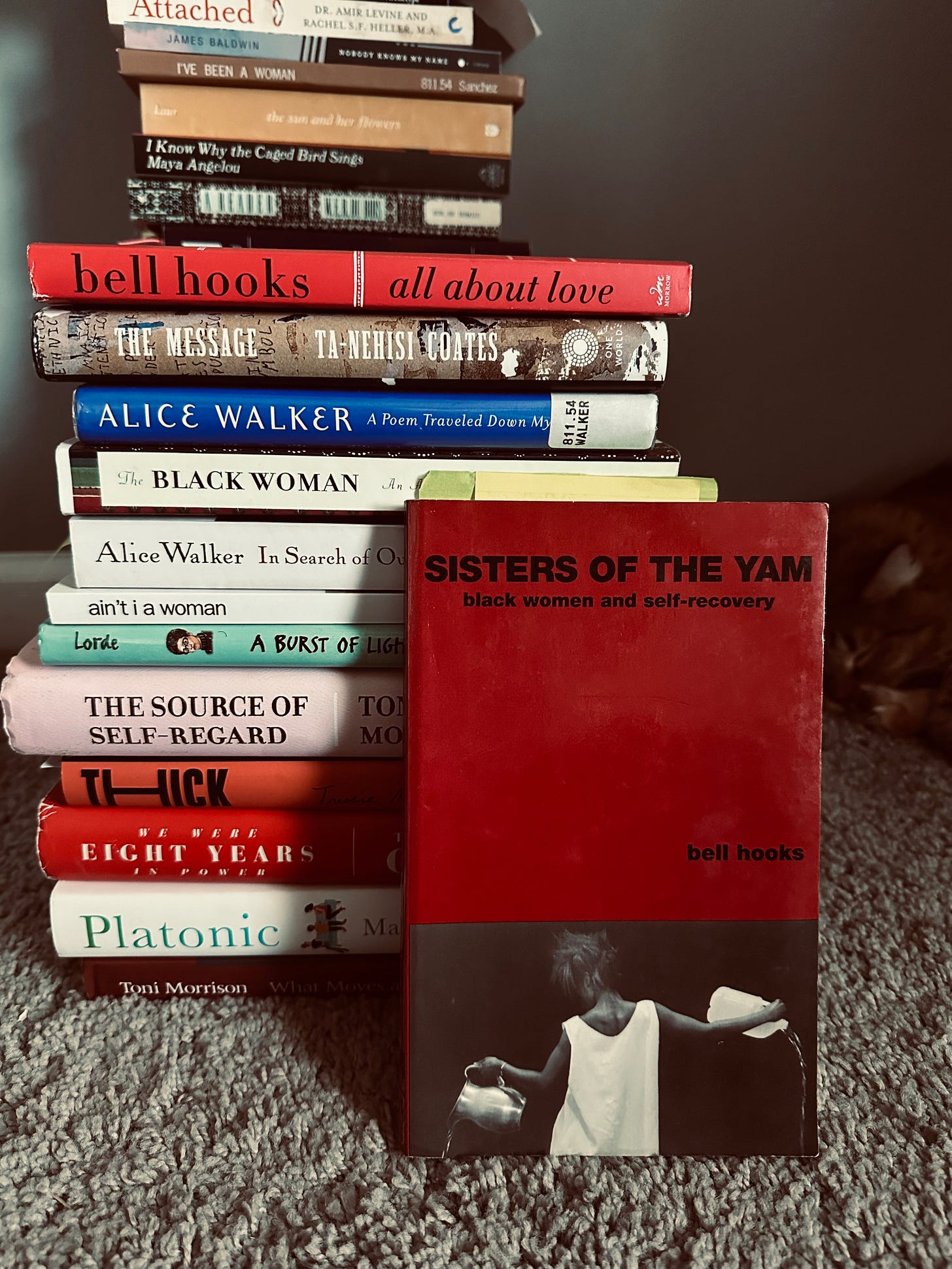

I had to learn to become comfortable alone and as a single woman. Initially, silence felt loud and piercing, and being alone with my thoughts felt hostile. Grasping that isolation during that period of my life was not the negative connotation I once associated it with. That time gave me a safe space to contemplate facets of the relationships I had left, how I contributed to those bonds, areas of improvement, and how to improve them. Reflecting on these events in 2021 I was unaware that this was my brick-and-mortar for building community. I was affirmed of my revelation a few months ago while reading Sisters of The Yam, by the late Bell Hooks.

“Black women have not focused sufficiently on our need for contemplative spaces. We are often “ too busy” to find time for solitude. And yet it is the stillness that we also learn how to be with ourselves in a spirit of acceptance and peace. Then when we re-enter community, we are able to extend this acceptance to others. Without knowing how to be alone, we cannot know how to be with others and sustain the necessary autonomy.”

I called my contemplative space “mental recess”. This occurred when I let my mind wander with intentionality. This place in my mind was quite literally a playground. My indecisive thoughts were the seesaw. My ideas, strategies, and plans were the funnel — needing further analysis and adjustments. Thoughts about love, parenting, my family, and my future were the sandbox. I romanticized my destiny heavily during this time. Daydreaming about the future felt childlike and blissful — gentle, like playing in the sand. Bucket list ideas and imaginations of a more adventurous version of myself were the swings. Those thoughts made me feel above my problems and free but needed much effort to be accomplished like pumping my legs swinging fast and high on a swing set. My thoughts and feelings about a less distant future, what was next for me, and how to move on and move forward were stiff and insecure — like standing next to the teacher at recess.

This mental anarchy —my contemplative space was the foundation for stillness. After some time, I found my way through the labyrinth of thoughts, feelings, and emotions by exploring their consciousness. Here, I learned the time and need for contemplative spaces do not expire. It is not work that can be put away or put off. Doing so is forfeiting space for assessment and analysis — deconstructing the uncertainties, and the how’s and why’s. Even if invasive, thoughts that occupy contemplative spaces became my meditation. Meditation shuts the vault of the contemplative space. What comes in will stay — this is stillness.

Frustrating myself, I pondered about situations I believed were resolved. I was talking about a particular problem with a friend. We discussed it a few times and I circled back to give her an update. While venting, I omitted what I once took accountability for. In my pursuit of justifying my emotions, I’d forgotten that part of the story happened. I rehearsed the situation wrong in my mind and heart for weeks.

I left the conversation feeling betrayed by my contemplative space. By my invitation, dishonesty found a way into an already arduous problem. Stillness joined me in the contemplative space as I meditated on the situation and the conversation with my friend. I then learned that truth-telling must be an active and consistent variable in my contemplative space and stillness.

In Introspection I was given the tools to extricate fragments of effective strategies and better facilitate my role in friendships and relationships. In isolation, I learned the depth of my human capacity as a dwelling place. Like many who have faith-based beliefs — I understand that we exist as three persons in three dimensions: spirit, soul, and body. Introspection helped define and assign duties to the three persons. The spirit is the contemplative space — as such the contemplative space is not a destination or a thing, yet your person is a space. The soul, existing between the spirit and body — is where stillness is found. Immaterial in substance with the ability to influence the body as it exists in separate dimensions. Stillness is a place that has to be located, yet abides in the soul. Truth-telling as the body is the member that must be exercised and made active. The sequential order of the three is spirit, soul, and body — as the spirit possesses the transcendent power to influence all three involuntarily. The spirit must inform the soul and thereby wills the body to act. Simultaneously this knowledge is the necessary preparation and foundation of friendship and evidence of community.

This understanding was not a seamless transition. It’s equivalent is learning how to ride a bike. Thinking back to when I was learning to ride a bike, I learned later than other children. Like others, I was not taught how to ride in one step. I began first by learning how to sit on the bike. The seat may or may not need adjusting and a certain posture must be maintained to ride a bike properly. I sat up straight and put my hand on the handlebars. I wiggled in my seat some then put my feet on the pedals. Sitting upright and pedaling straight was difficult but I got it down after a few tries. Combining and continuing all three motions and learning how to turn was more difficult. Braking was even more challenging. Then riding with environmental factors — pedestrians, other bikers, in and around traffic. Also internal factors — fear of falling, judgment, depth perception, etc.

After attaining the knowledge of my full humanity (spirit, soul, and body), I found that with much diligence to decipher between my spirit and soul, in due time the two begin to exist in tandem. Along with the body and the consciousness of the tandem, stable symmetry is established and discipline remains.

A part of discipline is understanding. The ‘why’ of discipline is as important as the what and the how. Awareness of the depth of my humanity that I newly lived with brought about the need to grasp its utility. To be knowledgeable and informed of the duties of the spirit, soul, and body is hardly sufficient. The same tools that I used at the beginning of my journey are the same that remained with me and helped me to find my footing by synchronizing their function: contemplative space, stillness, and truth-telling. Riding the bike was the only way to practice and improve.

My friend group hasn’t changed much since my freshman year at the University of Memphis. A few new friends have come and stayed. Some old friends have left and stayed gone, and proximity has changed with all or some of my friends at one time or another in our lives. It has been my experience that this is the essence of friendship as an adult. I am not and have never been the woman who claimed not to have any friends. Though I likely will not be a bride with a bridal party of ten plus — the people I am friends with have enough personality to fill a stadium. Being friends with eclectic men and women has given me demonstrative insight into engaging in and building community.

In preparation for her move to Florida, my friend and I had the delightful pleasure of spending days with each other sporadically over the summer. We had not spent more than a few hours with each other since high school. On one particular night, we rode to the gas station to replenish the wine we had drank while chatting and watching our kids hang out earlier that afternoon. We shared deep laughs about little things while choosing which wine we would buy. On the way out we cackled some more after I mentioned how handsome the clerk was. We listened to our favorite songs by Jazmine Sullivan on the short drive back to my house. She parked her Jeep and we sat outside for a while when I requested that she play our song. You Don’t Know My Name by Alicia Keys is a song that we’ve drunkenly sung at the top of our lungs, sometimes tearfully many nights. This night was no different. You Don’t Know My Name was a vehicle that drove us down memory lane and tangibly connected us to every memory we made of that song. Telepathically we both understood we were cruising and began to reflect on our decade-plus friendship aloud.

Teary-eyed we talked about how we matured throughout our friendship and learned how to disagree fairly and appropriately. We discussed what we said to each other that hurt us and applauded each other for overcoming situations that tested our friendship. As I was thinking of the external conditions that we both endured and how we established a rhythm as a duo that we could keep up with I shared a deeper part of my heart with her. My voice cracked as I told her that she was my greatest relationship to date — citing that she is and had ventured with me through the summit of a mountain, the valley, the foot, the hillside, every slope, and still our friendship remained.

I encountered many valleys in my friendships during my time of re-entering the community. Those valleys seemed lonely, and even though I was near my best friend and other friends at the time, I preferred to walk alone. I also believed I was alone. This was not due to an absence of friendship. Post-breakup, during my time of isolation, I was limited in engagement with friends, but I have never been friendless.

As intrapersonal as seclusion may seem, when I was not becoming more aware of myself —I learned what connections were not present or lacking at the time. Interestingly, the more I came to learn and understand the dimensions of myself it pulled out of me this necessity for closeness with my friends. I believed this need was simply for proximity. I believed the desire for closeness was to be present with them no matter what the environment or activity. My re-entry to community began by agreeing to everything I was offered or invited to. I thought the cure for the loneliness I felt was to connect with anyone and everyone that I could. I went on dates with men I knew I was not interested in believing that though I had no romantic interest maybe we could cultivate a friendship. I went to whatever function or gathering my friends invited me to even if it were for family members or friends of that friend. My strategy repeatedly failed to foster connections with new people or those I already had a friendship. During that time I did observe something valuable that caused me to adjust my approach to connections.

Regardless of the activity or occasion, in any environment that I was in for longer than two hours, whether it was myself and another or a group of us — there always came a shift in the conversation where facades disappeared. Language undressed and became naked in front of all that partook. There were fewer barriers to realism, even if the things that were said were regrettable to the one who spoke them. The liminal space of vulnerability and whatever followed after is what I found to be the most engaging. It felt like a meaningful connection to me. This taught me that it was not merely proximity or closeness with my friends that I needed — it was a kind of intimacy that I was ignorant of existed.

In 2016 Shasta Nelson author of Frientimacy spoke at a TEDx Talk at LA Sierra University dissecting the three requirements of healthy friendships. Shasta defines frientimacy as a relationship where both people feel seen safely and satisfactorily. Frientimacy does not just happen; it is formulaic. It consists of positivity, consistency, and vulnerability. She further states that our loneliness is not because we need to interact more but because we need more intimacy.

If I had known of Shasta’s book or watched her TEDX Talk during this time, I would have considered myself diagnosed and cured in one sitting. That’s not how things transformed, but I am happy to again have found language to echo that moment in my life’s sentiments.

After realizing what was absent in my friendships, I retreated to my contemplative space and sat in the company of stillness to understand better my responsibility for the reason that I was lacking in these dimensions of friendship. I contemplated for a while about examples of the frientimate dynamic that I have seen in real life and fiction examples. Max’s Insecure is my comfort show. I can’t recall an episode I did not watch as soon as it aired and I rewatch it often. Issa Rae’s mirror bitch and my inner monologue are practically the same person — at times a little more or less awkward. I cannot think of a scene that is not resoundingly relatable to me or my millennial friends.

Issa and Molly’s friendship invaded my mind. All five seasons of the show are filled with instances of the three angles of the intimacy triangle: consistency, positivity, and vulnerability. Stillness invited me to think of which aspects of frientimacy were missing and from what friendships. Re-entering community is a collaborative effort. Community is the constant juxtaposition of the sustaining effort of how well you collaborate with yourself and with those you call friends. The domestic work of self must be done by you and for you, though the work should not end with you. I am thinking of Audre Lorde’s profound definition of self-care. I am thinking of her care for self as a sustaining power of care for others:

Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare. - Audre Lorde: A Burst of Light

Political warfare employs all the means at a nation’s command, just short of war. As black women, voluntarily or not our existence is a cultural infantry. On the front lines robbed, bleeding, wounded, and bruised, by anyone who has had their way with us yet, our brokenness still yields useful innovation. Audre’s definition of self-care is the yoke of community and political warfare. Examine the nucleus of community and self-healing. Certainly, the wellness of livelihoods abides at the center of healing, but whose? Solitude which employs the healing, knowledge, and understanding of self is the leg of a table. utility of self is another leg on the table. Fruitful re-entry to community is the third leg. For all parties, healing and health are the tabletop in which we dine and share with our communities and others that may come and go. The reward of eating at the table is the continuity of nimbleness and collaboration with self and community.

The very thread of the fabric of community is love. The omnipresence of love is a necessity in every stage of community. The journey is not point-to-point and certainly not a straight line. Community is a spectrum that can and should be traveled through and explored throughout our lifetime, and you exist there somewhere at all times consciously or not. As it is a spectrum you are the beginning and end of the prism — originating and concluding with self. As you travel you come to a place of understanding whereby you realize your bonds and relationships can only be as healthy and as fruitful as the self-work you have successfully done.

In Sister’s of the Yam Bell Hooks wrote “Now I am more confident that community is a healing place. As black women come together with one another, with all the other folks in the world who are seeking recovery and liberation, we find ways to get what we need to ease the pain, to make the hurt go away.” Avoidance, escapism, and skipping steps will leave parts of the whole missing or fragmented. This is a willful forfeiture of healing. The cracks in the foundation (you) will spread. The work must be done—not to be confused with completed. You are the step, hallway, door, entry, and community capacity. The truancy of self-work is not solitude or loneliness; it is self-inflicted exile. You will have abandoned your greatest and most important relationship with whom you can never be separated. Do the work to arrive at loving yourself. Love yourself well to better love those you choose to be in community with.

Bibliography:

Hooks, Bell. (2015). Sisters of the Yam: black women and self-recovery. Routledge.

TEDx Talks. (2017). Frientimacy: The 3 Requirements of All Healthy Friendships | Shasta Nelson | TEDxLaSierraUniversity. In YouTube.

Lorde, A. (2017). A Burst of Light: and Other Essays. Ixia Press. (Original work published 1988)